Though it’s been a few years since the the FDA’s Unique Device Identification (UDI) rules came into effect, there remains quite a lot of confusion among medical device manufacturers about exactly how to label products.

Back in 2013, when the new rules were first implemented, many companies had to go through expensive and time consuming changes to their work flows. Many had to upgrade their hardware, changing the size of packaging and investing in new printers that could handle the demands of UDI, like our ThermaPrint 64.

Implementing an effective UDI labeling procedure from scratch is much easier, as long as you both understand the codes and have the correct equipment. Today, I’ll take you through the way that UDI codes and UDI printers work, in order that you can plan your workflow around what you actually need.

The Basics#

In principle, understanding UDI labeling requirements is pretty simple. Every medical device label needs to carry a number of key pieces of information, as well as a code that is unique to it. The majority of the information about a particular device is contained in a master database, the GUDID, which contains roughly 60 data elements per device.

Each device is linked to the database via a unique number, and this allows a huge amount of information to be retrieved about each item. This data includes basic information such as batch number and expiration date, but is also linked to records which detail adverse incidents and compliance accreditations.

The Differences Between Identification, Tracking, and Tracing#

In practice, UDI labels are used for a variety of processes, and there can be some confusion between these. Simply put, UDI labels are used for three things: identifying devices, tracking them, and tracing where they are. Let’s take a look at each in turn.

- Identifying devices allows manufacturers, authorities, and caregivers to look up specific characteristics of devices, and is the primary purpose of UDI. The UDI number on each label is used as a search key on the GUDID, allowing the user to access all the information held.

- Tracking is the process of recording which patient received a device. GUDID does not hold this information, and device manufacturers need not worry about it, except to note that the UDI on their devices will be used by caregivers to track devices in their own work.

- Tracing relates to the process of tracing the companies and entities that the device has been shipped to. Though the UDI number also forms a unique key for the purposes of tracking these movements, this process also does not effect the information stored on GUDID, which contains no such records.

Over the past few years, some device manufacturers have been concerned that patients may use a UDI to determine the number of devices, or the serial numbers, that the company has produced. This should not be a concern – access to the UDI, by itself, does not allow the public to access lot numbers, serial numbers, etc.

These three processes may be visualized as follows:

How UDIs Are Constructed#

As will be clear from what I have already said, the identification system consists of two parts – the UDI that is actually printed onto each device, and the information stored in GUDID about it.

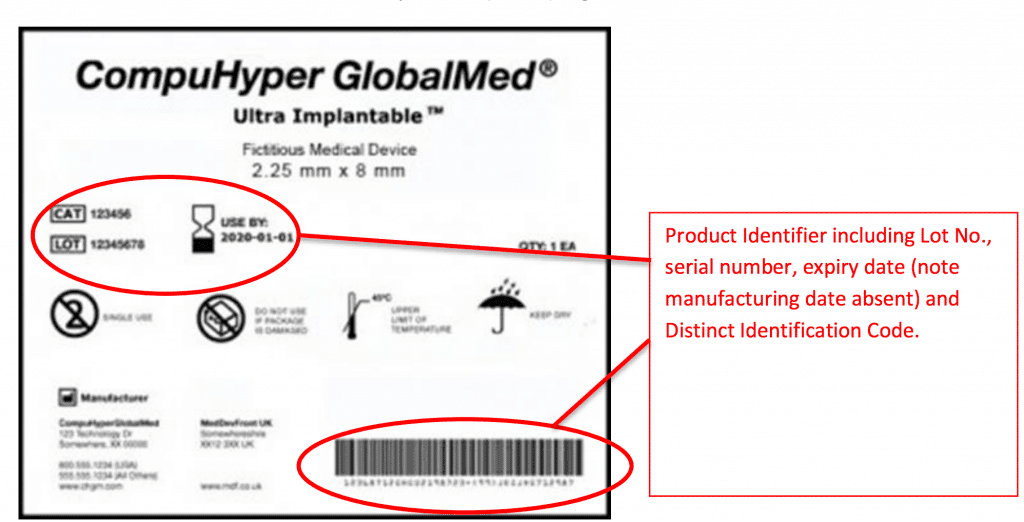

Bear in mind, also, that sometimes the terminology used here is a little hazy. When we talk of a “device label”, sometimes there is no physical label. A UDI label may be printed directly onto the device itself, or appear on packaging.

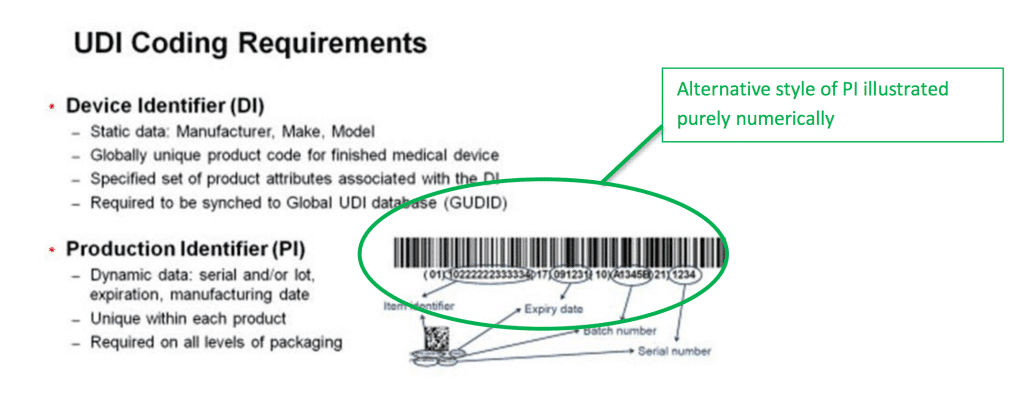

The UDI itself is made up of two parts. One of these in mandatory, and the other is voluntary.

- The Device Identifier (DI) is the mandatory part. This number is unique to the version or model of the device. If the device is re-designed, even slightly, the DI changes to reflect this.

- The Production Identifier (PI) is not mandatory, but is in widespread use. Many manufacturers use them to track production and batch numbers, but if they are not in use they do not need to appear as part of the UDI itself.

There are several further requirements when it comes to generating and producing UDIs. If you use any optional PI codes, they need to appear as part of the UDI in two formats – human readable, and machine readable. In practice, making a UDI machine readable means printing the number as a barcode.

Note, also, that there is a prescribed date format for any dates that occur as part of a UDI – YYYY-MM-DD – and that electronic devices need another date format again.

Implementing UDI Labeling#

Manufacturers do not produce DIs themselves. Instead, they must have a contract with an accredited agency who assign a block of numbers. This is done in order to ensure that each DI is unique. To date, FDA has accredited three agencies: GS1, Health Industry Business Communications Council (HIBCC), and ICCBBA.

The UDI must be printed onto each device’s label, but also must appear on any packaging that contains the device. Where multiple devices are packaged into the same unit, there is a separate DI, to be printed on the package, that represents the number of devices contained within.

The UDI need not be printed on every single device. If the device meets the following criteria, though, the UDI must appear on each individual device:

- The device is intended to be used more than once.

- The device is intended to be processed before each use.

- The device must have a UDI on its label.

Printing UDIs#

Beyond the administrative requirements of the UDI system, it is also important that your hardware can handle the level of detail required. Put simply, this means that you need a printer that can print hundreds, if not thousands, of unique numbers. This, in turn, requires that your hardware has enough memory to handle this data.

In practice, this means investing in a printer that can print on a variety of materials, and handle large runs of unique labels.

Updating GUDID#

GUDID must be populated by the device manufacturer for every device, and this information must be linked to every UDI.

There are two ways of doing this. One is to use the web-based interface for GUDID. The other is to submit XML files directly to the database. As I’ve said, there are about 60 fields for every device in the database, but note that not every one is mandatory, and that the level of information required varies by the type of device. Some are also populated automatically.

UDI And Other Systems#

Lastly, note that implementing the UDI system will have effects on your other processes. Specifically, the UDI procedures call for your quality control system (QMS) to include a check that the correct UDI is printed onto each device.

If implemented intelligently, however, the UDI system can have great benefits for device manufacturers, providing a ready-made unique identifier. Quite apart from allowing external agencies to trace and track your devices, these numbers also provide you with a rigorous system for tracking the same devices through their production processes.